Beautiful Landscapes

Photographies et collages, depuis 2006Etienne Bernard, 02

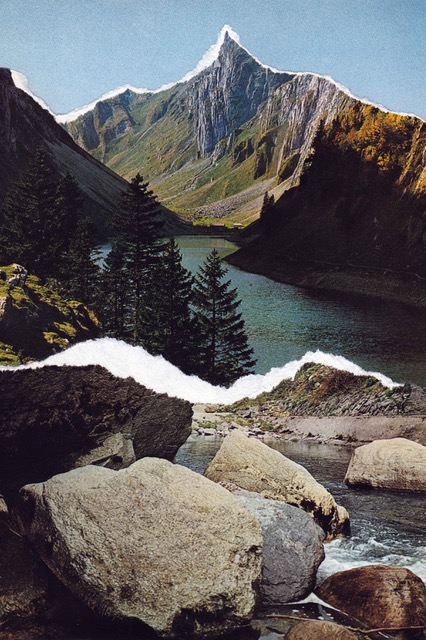

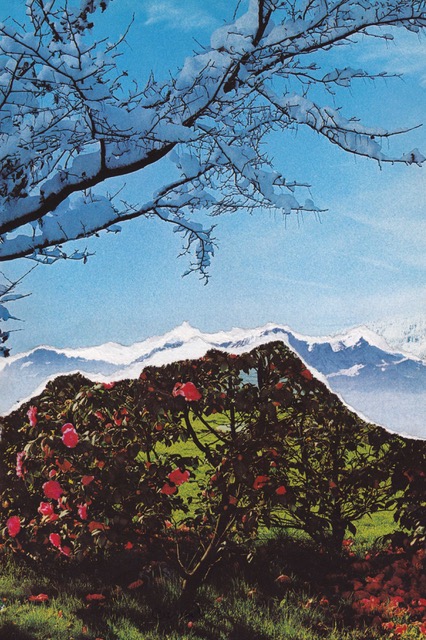

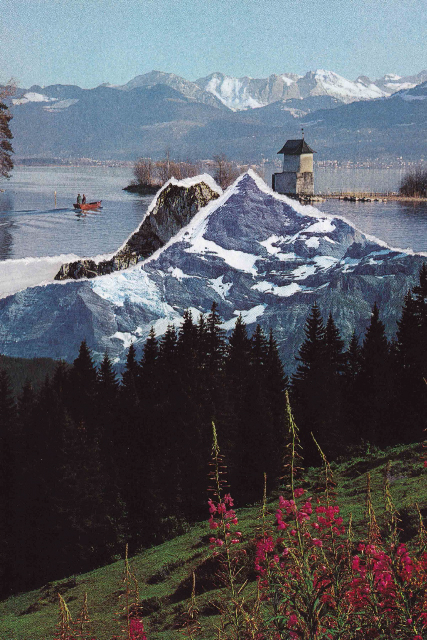

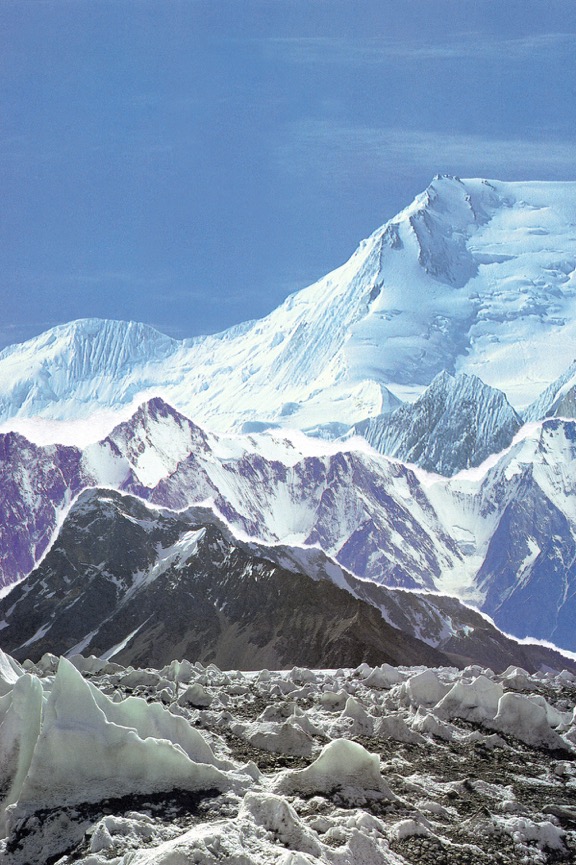

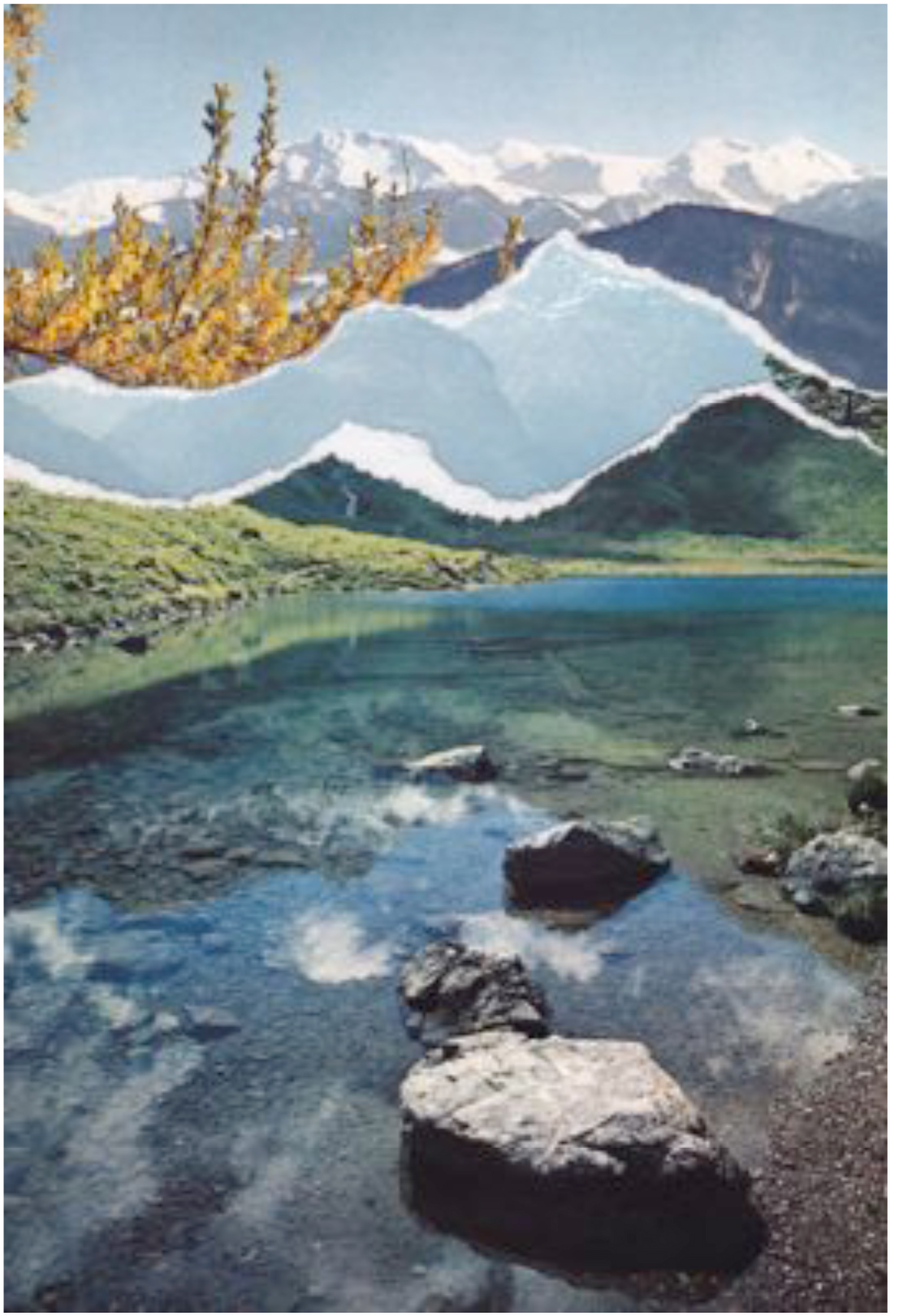

Dans un traité intitulé À la découverte du paysage vernaculaire en 1984, l’américain John Brinckerhoff Jackson définissait le paysage comme une succession de traces, d’empreintes qui se superposent sur le sol, comme le lieu de décantation des expériences humaines successives. Difficile de ne pas voir dans la série des Beautiful Landscapes que la jeune Pauline Bastard mène depuis 2007, une prolongation amusée de son propos. Minutieusement déchirés des pages de quelques manuels de géographie ou magazines de voyages, les fragments d’icônes paysagères viennent se superposer et se conjuguer pour former de nouveaux panoramas alpins. Et comme le dit leur titre, ils sont forcément beaux et à contempler. À l’évidence, le principe plastique employé se veut évocateur de la construction paysagère par sédimentation géologique et culturelle. Mais à travers les manipulations finalement relativement simples de la déchirure, la composition puis la numérisation, se lit également une synthèse poil-à-gratter et assez jubilatoire de la grande histoire iconographique de notre environnement naturel et de ses canons blockbusters. Et tout y passe! À commencer par la théorie du sublime de ce cher Kant, ici représentée par des sommets enneigés baignés de soleil dont la beauté n’a d’égal que l’inaccessibilité soulignée par la scarification affligée à la feuille de papier. Bastard n’épargne pas non plus le romantisme désuet de la scène laborieuse aux champs dont les faucheuses d’alpage sur offset N&B se livrent à l’observation contemplative d’un personnage 100% friedrichien en costume. Un peu plus loin, les analogies formelles entre pitons rocheux et épines faîtières des habitations d’altitude renvoient aux études anthropologiques et topomorphiques qu’aurait sans nul doute menées un Aby Warburg perdu au pays du Beaufort. Etc, etc. Comme quoi, avec une pile de photos arrachées et un bon scanner, il n’est pas impossible de digérer plus de cinq siècles de représentation paysagère ! Et c’est justement cette malicieuse habileté de Pauline Bastard à refaire dans la réinterprétation que la curatrice française Bénédicte Ramade a choisi de mettre en perspective dans la brillante exposition Rehab à la fondation EDF à Paris.

In a treatise titled À la découverte du paysage vernaculaire/ Looking for the Vernacular Landscape, written in 1984, the American John Brinckerhoff Jackson defined landscape as a succession of traces and imprints overlaid on the ground, like a place where successive human experiences are decanted. In the series of Beautiful Landscapes which the young artist Pauline Bastard has been at work on since 2007, it is hard not to see an amused extension of Jackson’s idea. Painstakingly torn out of the pages of one or two geography handbooks and travel magazines, the fragments of landscape icons are superposed on one another and combined to form new Alpine panoramas. And as their title tells us, they are perforce beautiful, and there to be contemplated. The visual principle used is obviously intended to be evocative of landscape construction through geological and cultural sedimentation. But by way of the ultimately relatively simple manipulations of tearing, composition and then digitization, it is also possible to read a jokey and somewhat celebratory synthesis of the great iconographic history of our natural environment and its blockbuster canons. And anything goes! Starting with dear Kant’s theory of the sublime, here represented by snow-capped peaks basking in sunlight, whose beauty is matched only by the inaccessibility emphasized by the scarification made on the sheet of paper. Nor does Bastard spare the outdated romanticism of the laborious scene with fields where women reaping mountain pastures on b/w offset give in to the contemplative observation of a costumed and 100% Friedrich-like figure. A little further away, the formal analogies between rocky outcrops and ridge peaks of mountain dwellings refer to the anthropological and topomorphic studies which would undoubtedly have led someone like Aby Warburg, lost, to the land of Beaufort. Etc, etc. Which is why, with a pile of torn out photos and a good scanner, it is not impossible to digest more than five centuries of landscape representation! And it is precisely Pauline Bastard’s mischievous skill in remaking in re-interpretation that the French curator Bénédicte Ramade has elected to present in the brilliant exhibition Rehab at the EDF Foundation in Paris.

︎HOMEPAGE